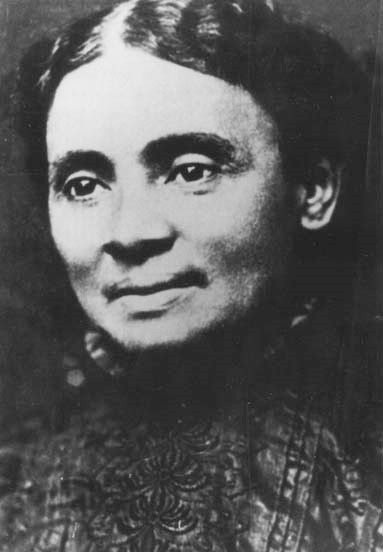

In honor of Black History month we would like to dedicate an article about Mary E. Britton (1855-1925) who was a student at Berea College from c1870-1874. A public school teacher and activist, Britton later earned a medical degree and became the first African-American female doctor in the state of Kentucky, practicing in Lexington.

Mary Eleanor Britton was born 1855 on Mills Street, in current Lexington’s Gratz Park Historical District, in Kentucky. Her parents, Laura Marshall and Henry Harrison Britton, were both free African Americans living in a slave state of Kentucky. Her father was a carpenter. Her mother, Laura Marshall, was a freed slave of a biracial ancestry, whose father was a well-known Kentucky public official Thomas F. Marshall. Britton’s mother Laura was a well-educated, intelligent woman, and a talented singer and a musician. Laura encouraged and instilled love for education, music and public service in both of her daughters from an early age. In short, her family was well respected, honored and trustworthy within the circle of prominent and affluent Kentucky families

She grew up in Lexington and, along with his sister Julia Britton, studied at Mr. Gibson’s school for colored youths in Louisville, Kentucky. Although, she grew up as a free individual, her siblings and her still experienced and witnessed the racial discrimination and inequality towards the black Americans. Yet, she and her siblings received the best education one could only ask for in Kentucky. She attended Berea College, at that time called Berea Academy, from 1871-1874. Since at that time the only available and possible career studies for females of any race was teaching and nursing, Mary Britton and Julia Britton Hooks chose to study teaching. She and Julia graduated in 1874 as the first two African American woman graduates of Berea College. Their parents unexpectedly passed away one after the other before the sisters’ graduation. Thus, after her graduation, Mary Britton sought employment as a teacher in order to support herself financially. In 1876, first she taught in Chilesburg, Kentucky and later continued teaching within the Lexington public school system.

Yet, although employed Mary did not stop pursuing her higher education, and attended and graduated with a medical degree from the American Missionary College situated in Chicago, Illinois. Since she had a great interest in medicine, she also studied at Howard Medical School in Washington D.C., and at Meharry Medical College of Nashville, Tennessee. Britton then started practicing medicine from her Lexington home. She specialized in hydrotherapy and electrotherapy, and by 1902, she became Lexington’s first African American woman physician licensed to practice medicine. Due to Jim Crow laws, the healthcare and medical treatment became even less easily available for African Americans at white hospitals. Thus, Britton made it possible for African Americans and treated her patients by using water and electricity.

Mary E. Britton treated patients from her home. Photo by Tom Eblen

Mary Britton was extremely active in public life of her community. For instance, she actively participated in Suffrage Movement, and later served as the president of Woman’s Improvement Club, which aimed at improving women’s social status, living conditions and economic improvements. In 1877, as a member of the Kentucky Negro Education Association she worked hard to help improve African Americans’ living conditions through legislative action. Moreover, from 1892 she served as the founding director of the Colored Orphan Industrial Home, which was an organization that, in collaboration with the Ladies Orphan Society, helped impoverished orphans and homeless elderly women with food, clothing, housing accommodation, receiving education and guidance on how they could eventually establish they lives. The building of that same Industrial Home is still present to this day as the Robert H. Williams Cultural Center and the Isaac Scott Hathaway Museum. It is a building, which has served as a nursing home and hospital through an entire century.

Moreover, in her writings for the American Citizen, the Daily Transcript, Our Women and Children, and the Lexington Leader, Britton wrote against the Jim Crow segregation laws, against usage of alcohol and tobacco, and expressed the necessity for societal reformation. In 1892 edition of Kentucky Leader, Britton argued in against the passage of the Separate Coach Law that had been implemented the previous year. The Separate Coach Law required that Americans of different races ride in separate – precisely, segregated – train cars, which supposedly kept every race equal, but not together in unity. Thus, Britton campaigned against the idea that all the races could be equal as long as they remained separated.

Mary Britton’s courage and compassion served as an inspiration to many within and beyond her community. One of them was author and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who dedicated a lengthy, yet thoughtful poem to Ms. Britton titled simply “To Miss Mary Britton.” The poem’s third verse recited the following:

Give us to lead our cause

More noble souls like hers,

The memory of whose deed

Each feeling bosom stirs;

Whose fearless voice and strong

Rose to defend her race,

Roused Justice from her sleep,

Drove Prejudice from place.

Mary Britton was an educator, physician, a journalist and a civil rights activist, who fully dedicated herself for the good of her people. She is another individual, who has reached the peak with her dedication to social work and civil activism. Mary Britton was not the only one who became a distinguished humanitarian and civil rights activist of her time. Her sister Julia Britton Hooks, also a Berea College graduate and a music prodigy, was part of the Memphis branch of NAACP and a civil rights activist against the segregation in public schools. The two sisters worked together in their public service and activism, thus achieving much for the best of their respective communities. Britton’s brother, Tom Britton, was a jockey of a great fame and talent. In his career as a jockey, he won the Kentucky Oaks on his horse Miss Hawkins in 1891, and came second in Kentucky Derby on Huron in 1892.

Mary Britton died at the age of seventy in 1925. She was buried in Cove Haven Cemetery. She was yet another African American woman many years ahead of her time. Gerald Smith, a history professor at the University of Kentucky, described Mary Britton as the one who “came out of that Berea tradition of a teacher who becomes a social activist.” Mary Britton truly believed in and followed the mission of Berea College. She was the change, educated in Berea College, which the American society needed.

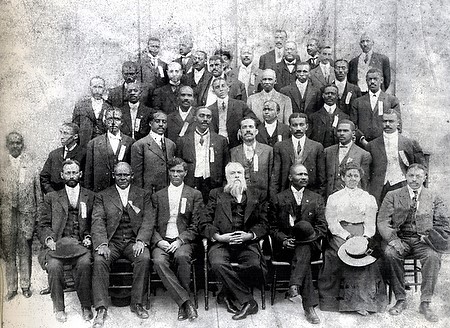

Dr. Mary E. Britton is surrounded by men at this 1910 meeting of Kentucky physicians, dentists and pharmacists. Photo courtesy of Thomas Tolliver.

Sources:

“Mary Britton was a woman ahead of her time.” The Bluegrass and Beyond. February 14, 2012. URL: http://tomeblen.bloginky.com/2012/02/14/mary-britton-was-a-woman-ahead-of-her-time/

Applegate, Emily. “The Noble Soul of Mary E. Britton.” Berea College Magazine. URL: http://www.bereamag.com/archives/2012/summer/features/strategic-planning-at-berea-college/

Women in Kentucky – Health/Medicine. URL:http://www.womeninkentucky.com/site/healthmed/M_Britton.html

Dunbar, Paul Laurence. “To Miss Mary Britton.” In Oak and Ivy. Dayton, OH: Press of United Brethren Publishing House, 1893. URL: http://www.libraries.wright.edu/special/dunbar/poetry.php?type=poem&id=348

Notable Black American Women, Book 2. Ed. Jessie Carney Smith. 1996. URL: http://books.google.com/books?id=ssMBzqrUpjwC&pg=PA55&lpg=PA55&dq=Berea+College,+Mary+E.+Britton&source=bl&ots=gVARmkl9Zp&sig=Jf85q37NpCAC10LcJfrWtcuPK3A&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ag1fUd3oEajZyQHUqYDICw&ved=0CF0Q6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=Berea%20College%2C%20Mary%20E.%20Britton&f=false

Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky, 1992. URL: http://books.google.com/books?id=8eFSK4o–M0C&pg=PA125&lpg=PA125&dq=Dr.+Mary+E.+Britton&source=bl&ots=2OhIIWvWTT&sig=rRARaVmhMg6ymCqciB85bS1LYDE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=dPJiUYG9HcKcqgGChoCICg&ved=0CGQQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Dr.%20Mary%20E.%20Britton&f=false